A Sunroom of One's Own

It’s a clear, warm Saturday morning in May, and my sunroom is full of light and the sounds drifting up from the sidewalk. Across the street, a black dog turns the corner sedately, trailing his human behind. On the sidewalk just below, a mother pushing a yellow stroller passes an elderly woman trundling a wire cart full of grocery bags.

Looking out from my sunroom, I can see the flat roof of Kimbark Plaza, just a block away to the south. In the other direction, twin rows of Victorian houses line South Woodlawn Avenue to the north. A block away along East 52nd Street, I can see the low profiles of modern townhomes built during urban renewal in the mid-1960s. As the sidewalk ballet—the stroller, the dog, the car alarm—plays out below, these taciturn buildings echo the stories of a century of history in Hyde Park.

◊

Hyde Park originated as a quiet, rural suburb of Chicago, and remained that way through the 1880s. A Mrs. E.G. of Hyde Park recalled, “We came here, that is my husband and I, in [1892]. It was regular country, with great meadows, wide dusty roads, and a bit of rolling country over to the southwest.” Another Hyde Parker—Mrs. Bennett, of 5807 South Blackstone Avenue—recalled, “The houses were large and spacious and surrounded by extensive lawns…. Most of the families kept cows and chickens.” This was a time when “mothers [of Hyde Park] worried for fear their children would fall into the water or get lost in the woods.”

The Columbian Exposition of 1893 set the stage for the urbanization of Hyde Park. In the years leading up to the Exposition, the Windermere, Del Prado, and other luxury hotels rose along the lakefront to house the fair’s wealthiest visitors. Further inland, smaller hotels, apartment buildings, and boarding houses were built between East 51st and 57th Streets in the heart of Hyde Park to serve as worker housing.

History books inform us that the Exposition brought more than 27 million visitors to Hyde Park, along with hordes of workers who built the fair’s “White City” and staffed the amusements on the Midway. Yet after the six-month run of the Exposition was over, and the crush of workers and visitors subsided, the fair’s enduring legacy in Hyde Park was a surplus of poorly designed and undesired buildings left behind.

“Hyde Park had been overbuilt in both apartments and homes during this hectic period,” wrote Paul Raymond Conway in his 1926 dissertation on Hyde Park apartment buildings. “The demand for housing accommodations fell [so much]…after the fair closed and the hard times came that entire buildings were sometimes devoid of tenants…so severe had it been that very very few apartments were erected during the next 10 or 15 years. It was a period of consolidation and recovery.”

The buildings had gone up in such a rush that the residents of Hyde Park had little time to think about them. As one woman recalled in 1926, “[The hotels] were put up very quickly for the fair trade, and were not considered a part of the neighborhood at all.” In the frenzy of the fair, many longtime residents of Hyde Park had believed that the tenements and hotels would vanish along with the visitors once the fair was over. Ruth R. said, “For 30 years people have been saying, ‘Of course they are horribly ugly buildings, but they are only temporary.’” The continuing presence of these leftover buildings—dirty, ugly, and full of “undesirables”—served as a warning of what Hyde Park might become if the process of urbanization were allowed to continue.

Even the apartment dwellers disliked the tenements. One student remembered: “I hated the apartments when I first lived in them, for I was so lonely and had so few friends. Again, my room was dark—oh, how I hate gloom!—as it had only one window that was surrounded (obscured) by another flat only about six feet away, and I could never see anything but a blank, grimy brick wall…flats are such ugly, straight, inartistic buildings.” Another resident said, “[An apartment] is so crowded, ugly, too dangerous to life and morals, and it is unhealthful.”

By 1910, apartment buildings were the only way to house the mass of families moving into Hyde Park. Many of these new arrivals were middle- and upper-class Chicagoans leaving deteriorating neighborhoods to the north and west. They were likely drawn to Hyde Park because of its bucolic condition and its excellent rail connections to downtown Chicago (at that time, the streetcar, the El, and the Illinois Central all passed through Hyde Park). The urbanization of Hyde Park first acquired urgency between 1910 and 1930. The population of Hyde Park nearly doubled between 1900 and 1920, and continued to grow rapidly through 1930.

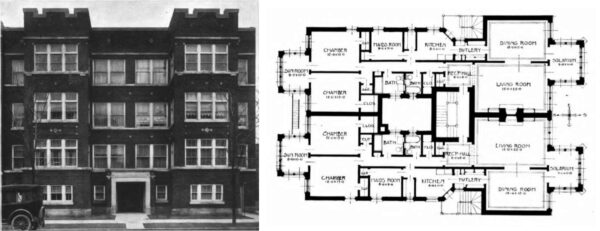

The six-flat walk-up apartment, with its characteristic front sunroom, was developed during this time in an effort to make apartment living more desirable. These buildings are Hyde Park mainstays. Today, six-flats are typical Hyde Park student apartment buildings. These buildings are so called for their six apartments (two per floor). All residents of the six-flat enter the same door from the street and climb a central staircase to their apartments. Each landing opens onto two apartments.

The apartment is usually organized with the public spaces—dining room, living room—at the front of the apartment, by the street, a sunroom projecting from the front of the building opening off the dining room and living room. The bathrooms and bedrooms, the private spaces of the apartment, open off a long hallway stretching from the entrance to the back of the apartment. Except for the large, boxy sunrooms in front, this layout was typical of apartments across the country.

The sunroom was Chicago’s unique solution to the problems of city life. In a typical tenement building, each resident’s apartment was discernable from the sidewalk only as a dark window in a flat wall, indistinguishable from its neighbors. The protruding sunroom bays of the six-flat apartments made the internal division of the apartment building intelligible from the street. The pitched roofs capping the third-floor sunrooms recalled the proud Victorian houses of South Kenwood Avenue and South Drexel Boulevard. The flexibility of the sunroom, as well as the extra light it brought into the apartment (a remedy to the darkness of the earlier tenements), no doubt contributed to its popularity as a building type during this time. To this day, the sunroom acts as a buffer between the life of the apartment and the life of the street. It enables a connection to the outside world, but doesn’t demand it. Three walls of casement windows admit a panoramic view of the surrounding neighborhood. In the sunroom, the sounds of passing trucks, arguing couples, and barking dogs rise plainly from the street. Looking across to the sunroom bay next door, one becomes aware of next-door neighbors. I am more aware of the surrounding neighborhood in my sunroom than anywhere else in my apartment.

The flip side of this is that, from the street, uncurtained sunrooms appear stagelit, their contents on display to all passers-by. For this reason, apartment dwellers seem to avoid their sunrooms. Despite this, the sunrooms provide the pedestrian with a sense of connection to the inhabitant within. The contents of a sunroom—a worn-out green sofa, a stack of books, a model ship—testify unavoidably to the life of its occupants. Through the sunroom, the pedestrian and the apartment dweller acquire a strange acquaintance in which neither sees the other, and yet each is aware of the other’s presence.

The addition of the sunroom made the apartment building interesting. Even more, the sunroom gave the apartment building the confident sense of place that, until then, had been enjoyed only by the single-family frame house.

◊

I’ve always found the modern townhomes lining East 55th Street unpleasant. Their (mostly) windowless faces seem unfriendly and the unrelenting beige flatness of the facades depresses me. Passing them on the sidewalk, I wonder to myself: Why are these buildings so bad?

As it turns out, there are developments of modern townhomes all over Hyde Park—and they’re not all bad. Like the six-flat walk-ups built several decades before, these developments were conceived of as antidotes to the urgent problems that Hyde Park faced at mid-century. And like the walk-up apartments, the modern townhomes are artifacts of their time. Some of the solutions they introduced work beautifully today, while others appear alien and unsuitable.

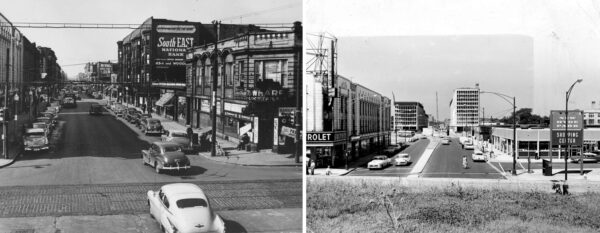

Hyde Park was transformed through the intervention of community improvement organizations backed by the University and by federal and state initiatives. These groups used authority granted by newly expansive urban renewal laws to seize and demolish entire city blocks. Once the land was cleared, architects were brought in to realize in brick and concrete the planners’ vision for a new Hyde Park.

The businessmen who put up Hyde Park’s walk-up apartments in the 1910s through the ’30s had accepted urbanization as inevitable. With the walk-up apartments they built and financed, they sought to accommodate the need for higher-density housing while providing apartment dwellers with privacy and a sense of individuality. The urban renewal authorities, by contrast, resisted the pull of urbanization. These authorities, led by the newly created South East Chicago Commission (SECC), sought to remake Hyde Park into a smaller, more tightly knit community attractive to young families with children. The architects hired to design the modern townhomes were tasked with interpreting and realizing this ideal.

The earlier six-flat apartment buildings had been criticized for their lack of neighborly feeling. Almost all of the modern townhome developments, like I.M. Pei’s townhouses and like The Commons, New Gardens, and Coop Square/Rochdale Place, sought to build a sense of community with courtyards and other common spaces.

Coop Square/Rochdale Place, a modern townhome development on the northern side of East 55th Street between South Dorchester and Blackstone Avenues, is a prime example of what the SECC sought to achieve. At Coop Square, Chicago architect Harry Weese gathered the units around an enclosed central courtyard with a sandbox and a tiny basketball court. Accessible only to the residents, the courtyard is a safe place for children to play and adults to relax. In front, there is a tiny strip of yard between the sidewalk and the front of the unit, where large windows allow residents to keep an eye on the street. This development is a safe haven for residents, but from the sidewalk, the locked gates and cast-iron fences pushed up to the curb are hostile and unwelcoming.

The Commons and New Gardens, two developments built after Coop Square/Rochdale Place in the mid-1960s, present a friendlier aspect to the street—perhaps because Hyde Park was by that time becoming a less threatening place. Both feature semi-public shared spaces. At New Gardens, south of East 55th Street between South Kimbark and Kenwood Avenues, units face onto two quiet, sunny courtyards. The courtyards spill down to the street over a wide, shallow flight of stairs. This small height difference gently marks New Gardens as a distinct community, without the tall fences and locked gates of Coop Square. The landscaped courtyard at The Commons, just north of Kimbark Plaza, is separated from the sidewalk by a modest brick wall and cast-iron gate. Both developments are clad in rough red brick, rather than the precast concrete and tan brick of Coop Square, and the textural richness of the brick and variation of the facade are a relief from the spare aesthetic that dominates East 55th Street.

Even I.M. Pei’s yellow-brick townhouses along East 55th Street that I so disliked were, I learned, responding in their own way to the circumstances of the time. So bleak and unfriendly from the sidewalk, these townhomes have generous back windows opening onto small private gardens. Many of the townhomes that Pei designed also share a semi-public central courtyard that, I can easily imagine, quickly becomes littered with bicycles, balls, and kids’ toys in warmer months. Inside, residents praise the, “efficient, warm, thoughtful use of space,” light, and “beautiful wood.”

Ironically, the shared spaces of the townhome developments often created community through conflict. Disputes between residents with children and those without were common: One resident of The Commons recalled the noise that local children used to make in the shared courtyard. She said, “Those kids would come out at seven o’clock in the morning. I said, ‘Oh my god, we got to do something about that.’”

“It was maddening!” said another resident. “[We] had meetings and explained the rules to the children. There was no bike riding and no ball throwing and no skating. They knew what the rules were, but you know…children are children.”

As an urban form, these courtyards reflected the collective unity of their residents in the face of the still-dangerous urban landscape. In the same way, the extreme flatness of the facades of Pei’s and Weese’s townhomes is harsh, but at mid-century it served as a statement of solidarity. The uniformity of these facades declared that the residents stood together as a bulwark against the physical deterioration of Hyde Park. If, today, walking along East 55th Street, the yellow-brick townhouses seem like fortresses, it’s because they once were.

This article originally appeared in print in Grey City, the Chicago Maroon’s quarterly magazine (pdf). This article provided the source material for Jane’s Walks in 2014 and 2015, focused on Hyde Park’s modern townhomes.

Thanks to Diane Herrmann for speaking to me and showing me around her home, an I.M. Pei E-model townhome, and to Jewel Davis, who lives in a Hyde Park six-flat apartment, for speaking to me about her experience of the six-flat sunroom apartments.

All photographs not otherwise attributed were commissioned for this article and captured by the skilled Matt Frankel.