Permanence and Program: Farewell to the American Folk Art Museum

Architectural critics and preservationists have been working themselves into a frenzy since the Museum of Modern Art announced last Wednesday its final decision to demolish the American Folk Art Museum building. MoMA’s announcement comes at the end of six months of extended deliberation, and MoMA has made it clear that this is their final decision. In light of this, the mainstream critics’ self-righteous outrage does more harm than good and obscures valuable insights into permanence, program, and flexibility in architecture.

The folk art museum building was designed by New York-based Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects in 2001. Underlying the design was the belief that the building should be tailored to the character and needs of the institution it was to house and that form, materials, and structure should respond delicately and exactly to the program.

The façade of the building is paneled with heavy slabs of tombasil, an alloy which critic Herbert Muschamp likened to, “travertine marble alchemically rendered into bronze.” The opacity of this façade and the rugged quality of its panels with their molten wrinkles and bubbles make a harsh contrast to the smooth glass façade of the MoMA next door. The façade of the Folk Art Museum is a gesture of solidarity with the art within, suggesting that the collection inside might be rougher around the edges, but also more sensuous and sincere than the modern stuff next door. The bronze face of the Folk Art Museum is a declaration of difference.

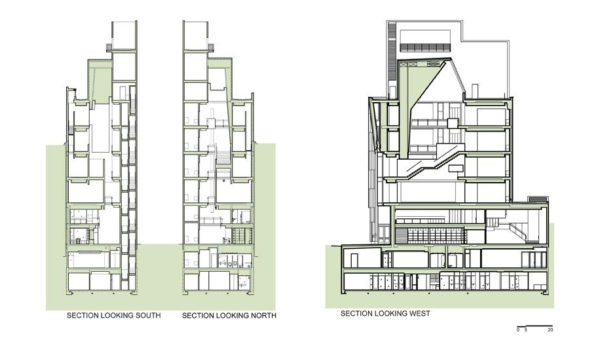

Inside, the architects created a winding pathway up through the museum, with extra-wide stairways displaying artwork and tall open spaces allowing views between different floors. Artworks are hung in unexpected places, and the sightlines through these tall open spaces let viewers experience pieces at different distances. Artworks are placed on balustrades and hung on concrete walls several stories up, as well as in traditional galleries. The collision of hanging styles made possible by the architecture captures neatly the mixed nature of the artifacts themselves.

At the same time, the architects sought to create a sense of permanence. Tsien said, “one of the things we learned is that we want, more and more, buildings that last. We want to avoid sheetrock and use materials with resonance and character.” The building is created using poured-in-place concrete, which means that the walls, the floor, the ceilings are all essentially part of the same continuous structure. This type of construction has the feel of permanence as well as its actuality – concrete is one of the most difficult building materials to destroy. In addition, because every part of the building is structural, it is much harder to modify.

When the MoMA announced its intention to demolish the building, it cited the distinctive (i.e. non-glass) façade and the disconnect between the floor plates at the folk art museum and the MoMA next door. If it was the idiosyncrasies of the folk art museum that created the conflict, it was the deliberate permanence of the building that made the problem intractable, even after six months deliberation. The New York Times reported that, “Because the floor plates support the façade, a reconfiguration would require much of the building to be dismantled and reconstructed.” Elizabeth Diller of Diller Scofidio + Renfro admitted, “We can’t find a way to save the building. You pass a tipping point where there’s not enough of the original structure to actually maintain its identity.”

There is a sense, then, in which the building contained the seeds of its own destruction. The folk art museum building was designed to fit its original inhabitants forever, not to adapt – but change is inevitable. True; with a different purchaser, the building might have been repurposed despite its resistance to change. Even a building as idiosyncratic as the folk art museum might have been converted to offices, residences, or performance spaces. But the architects’ design philosophy gambled the flexibility and future of the building against the ideal of creating a perfect space for the folk art collection. The dreadful paradox is that what made the building great – the sense of permanence it evoked, the rich materiality of concrete and bronze, the unique interior spaces it created – also led to its destruction.

Those who have vilified the MoMA argue that, as a museum, the MoMA holds a public trust to safeguard the folk art museum building as a work of great architectural value. Some critics have even imagined the building as an item in the MoMA’s collection. This conception of the building is a mistake. Reducing the museum to an object, a piece of art, is to consider only its aesthetic and formal qualities, and to do so is to ignore those qualities which make it a building. A building is such because it is designed to be used: Vitruvius’ utilitas.

The MoMA is demonized because its decision is judged by a standard which disregards the present context of the folk art museum in favor of the architects’ good intentions and the fit for the original occupant of the structure. The pens of the critics suspend the life of the building in the instant that it left the drawing board. But try as critics might to hold back the press of time, the fecund city pushes on relentlessly. The building must be judged in its current context, and part of that context is its usefulness as a space to be inhabited.

Ah, the protesters say – but the building would be perfectly useful if not for the damned expansion of the MoMA. Expansion is made a dirty word. Yet – if anything, expansion should be good. Paul Goldberger admits, “MoMA is as compromised by overcrowding as any museum I know…Lowry [the director] envisions the expansion as a way of creating much needed breathing space.” So while the expansion of the MoMA is regrettable in its consequences, it is not the sign of moral corruption that critics would have us believe.

The MoMA must bear responsibility for the tragedy of the demolition of the folk art museum – and it is a tragedy, if only because the building was loved dearly by many museumgoers. But it should bear that responsibility as the sad result of a Hobson’s choice forced by the nature of the folk art museum and not as a badge of ‘cultural vandalism’.

The folk art museum was an eccentric, friendly building that enlivened and enriched the urban life around it – Herbert Muschamp once called it “companionable”. We cannot do without such structures, buildings that are dynamic, brave, and richly memorable. It is true that the construction of such precious buildings is a gamble, that it comes at a price – but the worst that could come out of this demolition would be a swing to the other extreme: in place of the folk art museum, a building that is generic and utterly all-purpose. We hope that, as it moves forward with plans for a new building, the MoMA will bear the responsibility of the demolition thoughtfully and look for meaning in its loss, mindful of the architectural promises and perils it embodied.

The cover image for this piece is by davidgalestudios.