I Have No Memory of This Place

When I first saw Sohei Nishino’s map of San Francisco at SFMOMA, I felt an inexplicable, irrational sense of resentment. Behind me, a teenager crowed to his friends: “I don’t even have to look at the label, I can tell that one is San Francisco.” Nishino’s map of San Francisco is instantly recognizable from a distance, but as I inspected its details, I felt indignant in spite of myself. Nishino’s city wasn’t the San Francisco that I knew. Missing were the familiar sights that dominate my memories of the city: Mission Street’s shabby bodegas and dollar stores; the bookshops and taquerias fronting on narrow, shaded sidewalks along 24th Street; the cliffs of Thornton State Beach, draped with spiky succulent sea fig.

Nishino’s Diorama Maps combine mapping and photography, two of our most powerful technologies for producing truths about places beyond our immediate experience. In recent decades, scholarship in critical cartography and widespread awareness of digital manipulation in photography have revealed each medium as purposeful and duplicitous. Yet this knowledge has done little to shake our faith in the truthfulness of either medium. Nishino’s show of cartographic photocollages now on view at SFMOMA explores the ease with which maps and photographs so often appear under the guise of truth. The two mediums are joined in Nishino’s work by an insight from cognitive psychology. Decades of research in the psychology of spatial perception have shown that maps, photographs, and lived experience linger and accumulate in the mind to form spatial mental models called cognitive maps. In his photocollages, Nishino uses cartography and photography to visualize his own cognitive maps. By combining these familiar media in pursuit of the internal and intangible cognitive map, Nishino sheds new light on the apparent truthfulness of maps and photographs.

Each of the artist’s Diorama Maps depicts a single city through thousands of his own photographs. Nishino wanders through the city on foot, snapping pictures from sidewalks and rooftops with a film camera. He uses every single photograph in the resulting collage, cutting and pasting contact prints to construct an expansive and personal image of the city. Nishino explained in a 2016 interview, “I create [my maps] based on my individual experiences and observations…everyone has a map of certain cities in their minds, depending on their experiences. That’s what I’m trying to capture.”

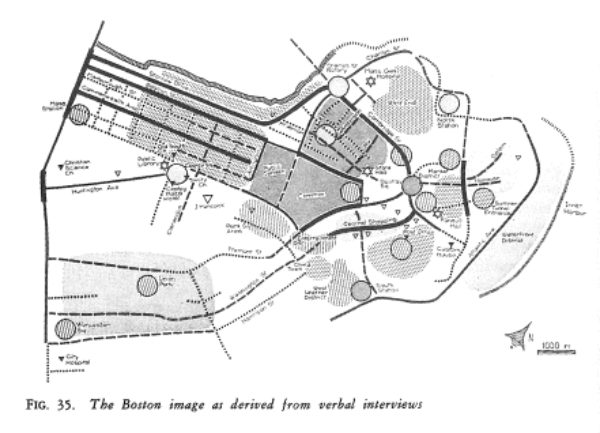

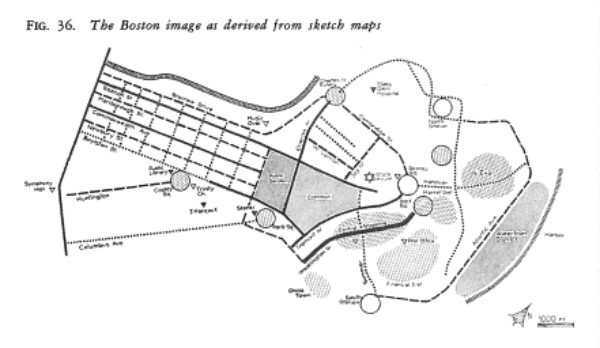

The notion that everyone has “a map of certain cities in their mind” was first systematically explored in the 1950s by urban planner Kevin Lynch. Using the tools of the psychologist, rather than the artist, Lynch and his collaborators interviewed dozens of city dwellers, asking them to sketch maps from memory or give instructions for traveling between two familiar places. Lynch synthesized the results of these surveys in schematic diagrams (below). These diagrams are tantalizing: they suggest that the accumulated experience of the city might be summarized and grasped at a glance. Lynch wrote that, “It was as if the map were drawn on an infinitely flexible rubber sheet; directions were twisted, distances stretched or compressed, large forms so changed from their accurate scale projection as to be at first unrecognizable…[but] the map was rarely torn and sewn back together in another order.”1 Lynch’s diagrams are remarkable in the way that they materialize mental maps, but are also narrow, inflexible, and purposefully stripped of emotional depth in favor of abstraction. Nishino’s procedure provides a new model for visualizing cognitive maps which is evocative and open-ended.

Nishino’s maps recall their cognitive counterparts in their deviations from textbook geography. Each Diorama Map is partial, fragmentary, and distorted. As in Lynch’s “rubber sheet” diagrams, landmarks, roads, and natural features are magnified, duplicated, misplaced, or omitted entirely. In Nishino’s map of San Francisco, Golden Gate Park and the Presidio are vastly enlarged, swollen with frisbee players and intrepid bathers, while the entire Southern half of the city is squeezed into a sliver at the bottom. The famous Victorian Painted Ladies match City Hall in height, and Twin Peaks appears twice, from different perspectives, as befits a landmark visible throughout the city. Each of these images is individually lifelike and credible. The distortions and omissions in the map arise from relationships between photographs. Indeed, the map is nothing more than a gestalt which emerges from the patterns of light and dark in the assembled images. The photographs wholly constitute the map. This extreme intimacy of map and photograph is novel, and it dramatizes the differences between the truth claims of each medium.

Susan Sontag wrote that, “photographed images do not seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it, miniatures of reality.”2 Historian of film Tom Gunning described this quality as photography’s truth claim. Gunning argued that the credibility of photographs as “miniatures of reality” arises from their unrivaled visual accuracy and their construction as the causal end-product of a deterministic physical process3. That is, Gunning argued that our scientific knowledge of the interaction between light and photographic chemicals endows the photograph with the appearance of objectivity. Nishino’s Diorama Maps extend Gunning’s argument by emphasizing that photographs claim a particular kind of truth: every photograph announces a personal, past experience. A painting or drawing may be inspired by past events, but it has no necessary connection to the past; the painter is free to show the never-was and the yet-to-be. Photographs are different. Our knowledge of the causal relationship between the photograph and the event it depicts marks the photograph as a representation of a past moment. Photographs are also distinctive for their mimicry of human visual perception. Produced by lenses which recall those in the human eye, photographs capture many of the essential features of human vision, like linear perspective. These qualities, familiar from our own visual experience, cue us to recognize the photograph as a representation of another person’s experience. In this way, photographs are always personal.

Maps, by contrast, claim universal truths. Where photographs invite empathetic identification, map projections show the world from a disembodied bird’s-eye. Divorced and abstracted from any corporeal vantage point or particular past time, the map seems unbound from particular human experiences. The impersonal map announces its contents to all viewers indiscriminately (it is precisely the universal quality of maps that give rise to disputes like this one on OpenStreetMap about whether Jerusalem should be labeled ירושלים or القدس). Further, maps derive authority from their usage in everyday life. We use maps to figure out when to leave or stay, where to go, and how to get there. There are other kinds of maps - historical, statistical, fantastic - but it is as navigation aids that maps are most widely and actively used. Unlike a photograph, which intrinsically represents the past, the map-as-navigation-aid is a promise about a place which anticipates future action. Such maps are useful only insofar as they correspond to the physical world they represent, and each map-aided journey completes a feedback loop which confirms the map as a truthful form by testing it against the real world.

By organizing his photographs in the shape of a map (or, alternatively, by populating each map with photographs), Nishino establishes a tension between the truth claims of these different mediums. The photographs personalize the map, making it a record of Nishino’s unique experience. At the same time, the map universalizes Nishino’s photographs so that each photograph appears as the truth of a particular place.

Standing in SFMOMA, it’s the overreaching photos, not the distorted maps, which I resent in Nishino’s Diorama Map of San Francisco. After all, we seldom have direct experience of the shapes of our cities. What’s more, cartographic distortions are commonplace in subway maps and in statistical maps, which claim to be all the more truthful as a result. Each photograph in a Diorama Map is bound by its cartographic context to fulfill the map’s promise of agnostic, reproducible truths about places. Yet this is an impossible task for a medium which is personal, fleeting, and fixed to the past.

We expect our cognitive maps to serve as truthful representations and reliable guides. Yet, because they are immaterial, made of nothing more than memories and sense impressions, they go uninspected; we seldom notice their gaps, omissions, and distortions. Someday, perhaps, technology could allow each of us to visualize our own cognitive map in a Sohei Nishino-style collage. Until then, Nishino’s maps will remind us to cultivate a healthy skepticism for spatial representation and to broaden our experience of the city by seeking the unknown: walking and biking to new neighborhoods, attending thoughtfully to details in the environment, and traveling unaccustomed paths.

Thanks to Abigail Kelly for reading this piece and giving wonderful, helpful feedback.

For further reading, see my full list of sources.