Three Excursions in Artificial Existence

The creation of a true artificial intelligence is likely still decades away, but as limited forms of machine intelligence become increasingly ubiquitous, questions about the relationship between we humans and our semisentient creations will become ever more pressing. NEAT: New Experiments in Art and Technology, on view this past fall at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco, offered a few compelling explorations of artificial existence. Arranged among unremarkable interactive visualizations and video artworks, these artificial beings were both formally inventive and technologically topical.

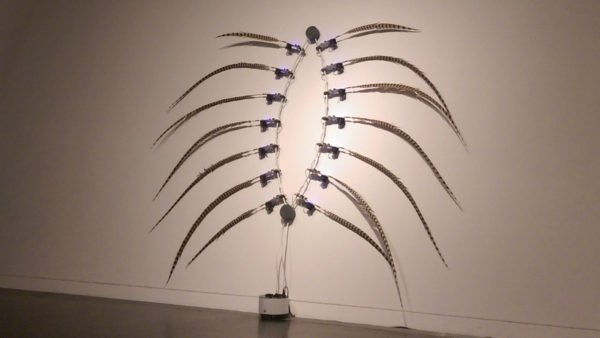

The most emotionally arresting piece for me at NEAT was Alan Rath’s Forever, a robotic sculpture with long brown feathers that could rotate forward and back on mechanized hinges. The feathers were attached at regular intervals to a lens-shaped frame leaning against the wall of the gallery; they looked like the legs of a giant beetle or the eyelashes of a great empty eye turned on its side.

When I turned the corner and saw Forever for the first time, I felt a flash of irrational fear. I’m not normally afraid or disgusted by insects, but my heart was pounding fast and hard as I stood in front of Forever. The movement of its many feathers, like the skittering legs of a giant, empty beetle, roused in me a primordial panic. The expressive power of this piece came from the way that the feathers moved in concert, sometimes undulating, sometimes flapping, then standing straight out and wriggling frantically before flattening abruptly against the wall again. The movement of the sculpture was purposeful, if unpredictable.

Forever was a hybrid creature, an eerie combination of organic and mechanical materials. As such, this sculpture offered a tantalizing (and uncomfortable) sketch of the kind of biodigital being that some scientists believe represent humanity’s most promising future. The springiness of the quills made the sculpture lively as it moved, even as the natural brown-and-white patterning of the feathers recalled the hapless pheasant or turkey from which they originated. Forever was an alchemical creation, one which appropriated and reconfigured the discarded artifacts of one creature in order to create a new being. The resulting creature was both beautiful, and a bit melancholy: pinned to the gallery wall like a framed insect, the sculpture appeared almost as if trying to climb the wall, to flee the museum. I was both fascinated and repelled by Forever, and I found that I couldn’t look at it for long before discomfort pushed me away.

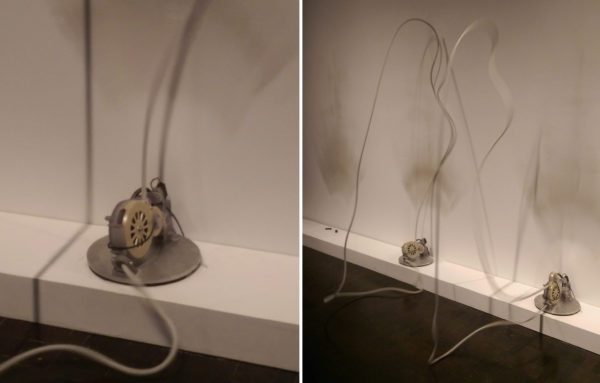

Paolo Salvagione’s Rope Fountain was a welcome relief from the intensity of Forever. Salvagione had constructed a sequence of sculptures, each consisting of a loop of white rope spun rapidly by a motor on the floor. Each loop appeared almost motionless, hanging in midair, its movement betrayed only by a penumbra of vibration about its silhouette and the humming of its motor. Each motor was on a pivot which allowed it to rotate parallel to the wall behind it. In addition, each motor had a nozzle controlling where the rope came out which was allowed to move forward and back. The regular motion of the motors along these axes caused the rope to move in unpredictable ways, swaying from side to side, stretching out horizontally, or rearing up to hit the wall behind.

The strength of Rope Fountain was the simplicity and transparency of the technology used to produce its complex, lifelike behavior. Standing in front of Rope Fountain, it was natural for me to attribute human motivations to the actions of the rope sculpture: curiosity, hesitation. The sculptures weren’t in the least anthropomorphic in form, but in their behavior, they reminded me of nothing so much as a line of dancers, moving freely and unselfconsciously. When a loop of rope twisted to dab at the ground, then recoil, I was reminded of a ballet dancer, eyes closed, exploring the world with their feet. Each rope sculpture was a line drawing, animated and lifted from the page, sketching a schematic being into existence. Each sculpture was also a creator, intermittently leaving faint smudges on the wall which collected to form dusty halos behind each loop of rope.

The technology used to produce these pieces was old - just a few motors, some rope, and a set of timetables to regulate the movement of each motor and nozzle. By exposing the technological apparatus that animated each sculpture, Salvagione demystified their behavior and allowed each piece to appear self-sufficient, autonomous. In all this discussion of Salvagione’s piece, I’ve struggled with “each” and “they”, and I would be remiss if I failed to acknowledge that I’ve been describing Rope Fountain in the singular, trying to convey the essence of the ideal form realized in each spinning loop. In short, Rope Fountain used technology, but it was not about technology - this was a piece about artificial beings and which questioned the minimum of what was required to represent a being.

Rath’s second robotic sculpture, called Soon, was a single enormous jointed arm mounted on a tripod. A floppy pink feather, of the kind used to make feather dusters, was attached to the end of the arm. As with Forever and Rope Fountain, the sculpture was capable of only a limited range of movement: the arm could rotate on its tripod and extend and retract, while the feather at the end was able to pivot freely in three dimensions. The sculpture was cordoned off from viewers by a circular border, like a circus ring. It was elegant, ungainly, absurd, pathetic.

Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom writes in Superintelligence: “Normally, we do not regard what is going on inside a computer as having any moral significance except insofar as it affects things outside. But a machine superintelligence could create internal processes that have moral status…there is at least the potential for a vast amount of death and suffering among simulated or digital minds, and, a fortiori, the potential for morally catastrophic outcomes.”

Soon suggested the possibility of a tension between the dual nature of artificial entities as tools created for human benefit, and as autonomous beings in their own rights. The robotic sculpture was far from a superintelligence - indeed, the feather duster attachment riffed on the dumb domestic devices that are ubiquitous today: dishwashers, dryers, washing machines, and vacuum cleaners. Soon was no more than a simple machine. Yet the gallery setting and the circus ring-like enclosure reframed the appliance as an actor, an individual (though a bit of freak): worthy of attention.

Sometimes, Soon would dance, spinning gracefully and then stretching to unfurl its feather with an elegant flick. These were the movements which seemed to elevate the robot above the level of “device”. Yet, at other times, Soon performed an absurd sketch of domestic labor, senselessly and ineffectually dusting the air before rotating to begin again. The circular movements of the arm, tracing the outline of the ring on the floor, echoed this temporal loop in which the device was trapped. It was the contrast between these two attitudes which made Soon appear forlorn, futile, pathetic. Strange as it seems, I almost felt able to sympathize with Soon.

Missing from any of these works (though handled beautifully by Camille Utterback in Entangled) was a convincing mode of interaction. Both of Rath’s pieces hinted at the possibility of interactivity, with Soon seeming to dust the noses of viewers, and Forever fluttering in time with sounds from the gallery, but in both cases the link between the environment and the actions of the sculpture was so subtle that it was unclear whether the appearance of responsiveness was due to accident or intention. Salvagione’s Rope Fountain didn’t offer even the suggestion of interactivity. The disinterested stance of these creatures was still compelling (though not altogether unfamiliar - think of teenagers or cats). Yet today, it’s the machines that can interact with (and track) us that are most interesting and frightening. Perception is an integral part of human existence; future artworks exploring artificial existence should use interactivity to engage this more deeply.